– Lalit Garg –

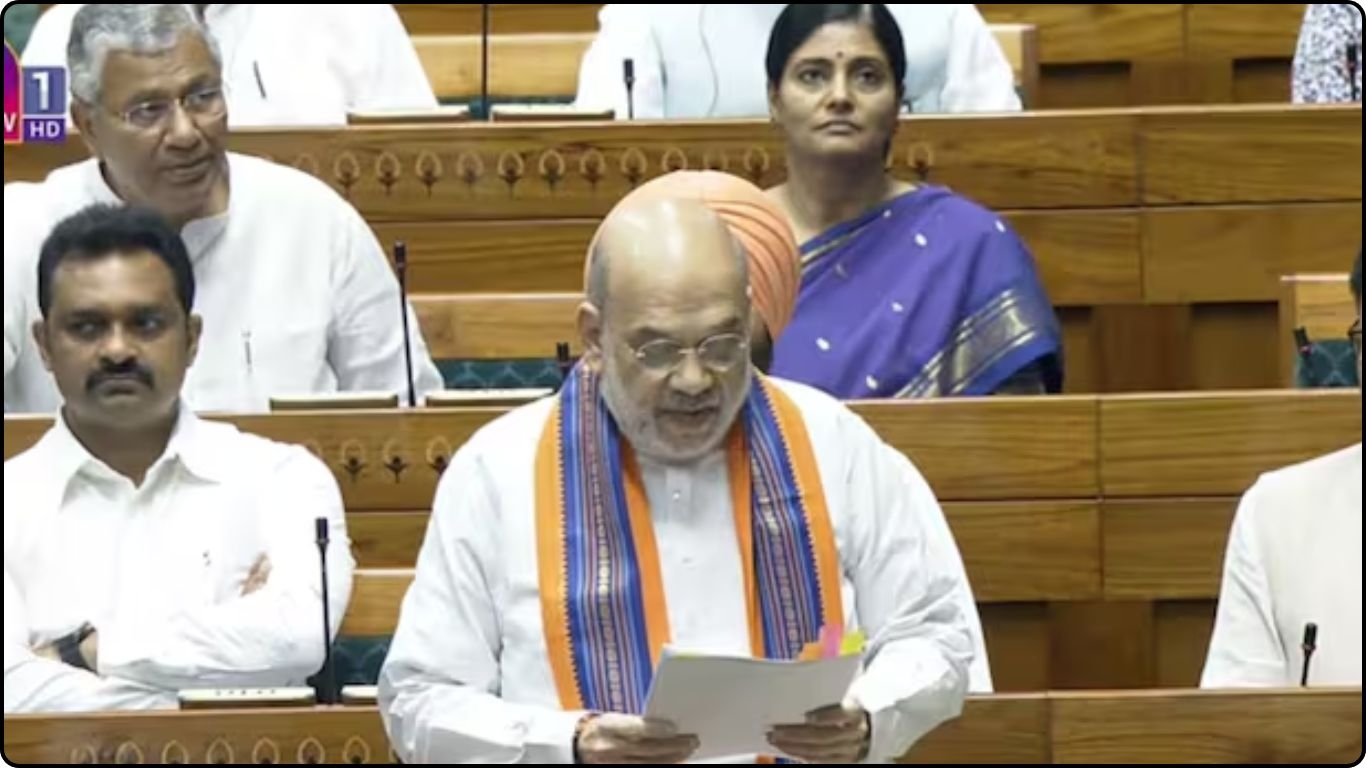

When the central government introduced a bill in the Lok Sabha providing that leaders facing serious criminal charges—including even prime ministers, chief ministers, and ministers—would be required to step down if arrested or detained beyond a certain period, the excessive uproar and opposition that followed was incomprehensible. A bill that advocates for honest, crime-free politics and seeks to ensure that the highest offices are occupied by leaders of integrity should have been welcomed as a step towards strengthening democracy. To create a ruckus over such a measure only undermines the dignity of democratic values. Displaying prudence, Home Minister Amit Shah proposed that the bill be sent to a joint parliamentary committee for review, a suggestion accepted by Speaker Om Birla. At this stage, instead of obstructing, the opposition should be reflecting on why such an ideal and necessary framework should not be established. Why should there not be a system where leaders occupying high offices are automatically compelled to relinquish their positions once they are arrested on grave criminal charges? What is the real problem with this? Why is the opposition becoming an obstacle in the path of moral and ethical political reform, raising questions about its own commitment to integrity? Does this bill not apply equally to ruling party leaders as well?

Since independence, politics in India has often been distorted by the dominance of criminal elements. The people expect their representatives to be honest, untainted, and men and women of character. Yet, reality has painted the opposite picture. Time and again, representatives are found entangled in serious crimes, and rather than resigning or stepping back from public life, they cling stubbornly to the chair of power. This obstinacy erodes the people’s trust and casts politics in a perpetual shadow of suspicion. The question has grown sharper: should individuals facing grave charges have the right to remain in positions of power? Can democracy ever be sustained on the foundation of crime and corruption? The answer is a resounding no. Unless politics is cleansed of criminal elements, good governance will remain a distant dream and the vision of a “New India”—developed, ethical, and just—will not be realized.

The time has come to legislate concrete, effective measures to rid politics of criminality. This is not merely a matter of electoral reform—it is about safeguarding the very soul of democracy. The moment a public representative is charged with a serious crime and sent to jail, he or she should automatically be divested of office until proven innocent. There should be no waiting for resignation, nor space for political pressure. Many leaders in the past have set such noble examples voluntarily, yet the conduct of leaders from the Aam Aadmi Party, Congress, Samajwadi Party, Jharkhand Mukti Morcha, and others has instead painted dark chapters—running governments from jail and clinging to ministerial posts. It is this dismal trend that has necessitated the present bill.

In a vast democracy like India, clean politics is not just an ideal, but an absolute necessity. When individuals with a criminal mindset sit at the helm of governance, they use the machinery of power to shield their own misdeeds. This corrodes democratic institutions and puts ordinary lives at risk. Corruption, muscle power, money power, nepotism, violence, and immorality thrive when politics becomes a sanctuary for criminals. The demand for honest leaders with spotless reputations has never been stronger. The people long for leaders who can inspire by the force of their personal conduct. Politics must return to being a medium of service and sacrifice, not ambition and manipulation. Those under even the slightest cloud of suspicion should step aside voluntarily. Only such traditions can restore politics to its nobility and dignity.

Crime-free politics is not merely a moral expectation; it is democracy’s compulsion. Without integrity and ethics in public life, neither good governance nor honest administration can take root. The greatest need of the hour is to legislate new frameworks that bar criminals from entering politics. Such measures will not only strengthen democracy but will also reassure the people that politics is truly meant for public welfare, not as a haven for criminals. This is the very philosophy of clean politics—that power should not be an asylum for the tainted, but a reservoir of moral energy for society. Only then can democracy regain its true soul and politics be seen once again as the symbol of service, purity, and honesty.

For years now, the nexus between politics and crime has been a matter of deep public concern. Citizens expect their representatives to be honest and transparent, with no blemish on their character or conduct. Yet, repeatedly, leaders mired in serious cases cling to high offices and manipulate the machinery of governance to protect them. It is in this background that the government’s proposed 130th Constitutional Amendment Bill must be seen as a historic step. The government describes it as an anti-crime, anti-corruption initiative, while the opposition remains unconvinced. But their disagreement raises troubling questions: why should the opposition appear as a defender of tainted leaders? Why would they risk tarnishing their own image by obstructing a measure aimed at integrity? The apprehension is that such a law might destabilize chief ministers or ministers in opposition-ruled states. But this exposes the real motive—the desire to preserve political convenience and power, rather than uphold moral accountability.

The opposition argues that the government could misuse this bill, forcing leaders out of office merely on the basis of accusations. But the truth is that unless laws are firm and unambiguous, the cleansing of politics cannot be achieved. If an individual is falsely implicated, avenues remain open for restoring reputation, but allowing those facing serious charges to continue ruling is a betrayal of democracy and its moral foundation. The example of Arvind Kejriwal attempting to govern from jail illustrates this distortion vividly.

As India advances toward the dream of becoming a “developed nation,” it must recognize that this dream cannot be fulfilled merely through economic growth or technological advancement. A transparent, honest, and clean political system is the bedrock of true progress. The infiltration of criminals into politics weakens democracy at its core and destroys public trust. Crime-free politics is not simply an aspiration—it is the very foundation of good governance and development. That is why this bill must be welcomed, for it marks the rise of a new dawn in Indian politics, one that seeks to anchor governance in morality, integrity, and public service. If the opposition continues to resist, it raises an inevitable question: does the opposition truly not want crime-free politics? Or are they simply afraid of losing their own tainted leaders? To safeguard democracy and strengthen its roots, this legislation is the need of the hour. Only when Indian politics is freed from criminality will New India become Developed India. From clean politics will emerge good governance, honest leadership, and a renewed confidence among the people. That will be the real victory of democracy.